Heap of Broken Images

Ashley Canty

January 10-February 21, 2026

Opening reception Saturday, January 10, 5:00-7:00 pm

Artist will be in attendance

Essay by Susie Kalil

In the front gallery of Ashley Canty: Heap of Broken Images—a mid career survey of the artist's work at Kirk Hopper Fine Art—densely layered, torn sheets of old musty wallpaper bulge, curl and jut out from the wall into the viewer's space, evoking crumbled archaeological fragments or decayed sculpture. The 12-foot-wide installation, reconstructed from Canty's studio wall in Nacogdoches, is frightening, welcoming and utterly captivating. To stand before the thrillingly dynamic centerpiece is to experience a portal to the past, waiting to be seen. At its core, the fractured, raw mix of wallpaper hones a language that is new and strange, turning the banal and familiar into something richly symbolic of our own fragmented, lost memories.

Gerasene Demoniac, 2025

At KHFA, Canty's 30 stitched works and collages begin in this way, with a suitably reverent discovery of wear and weatheredness. They are pieces of history, time capsules worthy of rejuvenation. As Canty understands it, we live in a time that devours the world. She resorts to scavenging wallpaper from homes being torn down or remodeled, rather than irreversibly consuming resources. Canty explains: "I first fell in love with wallpaper when I found it hidden behind paneling in a closet in our old house. I loved thinking about who might have spent the time picking it out and all the plans for it—the beauty they must have wanted. I love the familiar smell of it—the way it reminds me of so many places and things. The way it conjures memory. I love the patina of dirt, water stains and fading that only age can give. After the wallpaper no longer served a purpose of decoration, it was just discarded. I wanted to replicate that connection—redeem it, transform it. These works are the simple act of seeking beauty in what is lost and forgotten as a study to better understand the world around me."

People move in and out of our lives, just as we change, move through and abandon our wallpapered rooms. Old memories resurface and people paint them differently; we learn to view them anew. What this requires is careful seeing, and Canty's works beckon us to contemplate the end that will come to our relationships, memories, desires—all the things that make us who we are. Heap of Broken Images celebrates the labor of making and the fate of what is made. The disciplined intensiveness of hand stitching allows Canty to share the hand of the artist with the viewer. Using the patterned format of a quilt, she cuts and lays out wallpaper as syntax to create clues that shape a latent narrative. When a "square" is assembled, Canty begins stitching the fragments—sometimes thousands of seams—in a time consuming process that transforms the swimming optical patterns into micro-environments. Each stitch binds and strengthens against further decay, but also makes one ponder time.

Indeed, transience is the force of time that makes a ghost of every experience. All of our time disappears on us. We are knitted into a day. We are within it; the day is as close as our skin. Yet our days have disappeared silently and forever. If the poet's job is to strip away layers of distortion to reveal and elevate narratives that have been hidden or erased, then Canty's stitched wallpaper pieces serve as metaphors for migration and the shedding of earlier lives. Shapes soar and sink, suggest weight and lightness, shift between geometry and references to the natural and cultural worlds. To her credit, Canty holds all the incongruities in tension, combining visual decay with an impulse both reflective and sentimental. She treats wallpaper as palimpsest, with each history layered over the one preceding it. Canty braids stories together with uncommon patience, achieving a taut balance of style and metaphor, pattern and spirit. Her ingenuity, planning and obsessive labor call attention to the sheer amount of detritus we pile up and leave behind.

Studio Wall, 2025

Canty is among an ever-growing number of contemporary artists who have rescued textiles from second-class status in the art world. In early years, she watched her father do tile and stonework, a process that requires precision for pattern and use of materials. Canty's grandfather, a surgeon, always answered in detail the many questions she asked about the diagnosis of patients, how cutting them open and stitching them back together was essential to their healing process. While studying art at Stephen F. Austin State University, Canty enrolled in a collage course taught by artist Mary McCleary, who provided a gateway for craftsmanship and drawing fragments into a unified, collective experience. Later, Canty became a caregiver to grandparents and family members as their memories and health faded, an experience that forced her to grasp the temporary nature of all things.

The show's title, Heap of Broken Images, derives from T.S. Eliot's powerful ending of self-description in The Waste Land (1922): "These fragments I have shored against my ruin." It sources, as well, John 6:12, "Gather up the fragments that nothing may be lost," a metaphor for the unity and spiritual nourishment provided through Christ. For Canty, our worlds are both beautiful and soul-crushing. We carry our regrets and our joys in equal measure.

The prevailing effect is how the present intrudes on the increasingly removed past. Canty's stitches, like furrowed lines, remind us of contours that shape stories and lenses of memory. The wallpaper pieces and collages draw on a rich repertory, nurtured by exotic, esoteric elements: geometric and figurative, organic and symbolic forms alternate, reduplicate and reverberate from one work to another. They correspond to the patching together of parts, of sewing the clothes that might bear a body through life and death—of grief, when new mourning clothes had to be stitched.

Canty cites a range of high and low influences, from the detailed fantastical imagery of Hieronymus Bosch, the lushly illustrated books on bird paintings of the world, to the tiny hidden treasures of Richard Scarry's imaginative stories for children. There are echoes of the 1970s and early 80s Pattern and Decoration movement—in particular, Miriam Shapiro, Valerie Jaudon, Joyce Kozloff, Tina Girourd, Alan Shields and Robert Zakanitch, who adopted a vast vocabulary of craft materials, ornamental motifs and pattern designs. Advocating an eclectic blending of sources in novel and unexpected ways, they embraced the serious, the sensual and romantic, favoring color and innovative textiles without regard for artistic hierarchies. Like her counterculture forebears, Canty takes pleasure in something considered trivial or minor and elevates it to heroic scale.

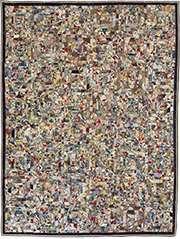

The surface of the show's title piece, the six-foot "Heap of Broken Images" (2025), is animated by a sense of delirious complexity. Weird little glyphs, faces and animals appear alongside abstract swirls, blobs and silhouettes. The longer you look at the repeating four pointed star pattern, the more you get out of it, until each little discovery and unlikely connection comes to feel like a personal revelation. Time worn hues—faded reds, muddy browns, dusty yellows—bump up against, or are interwoven with eye-popping reds, greens and oranges.

The Cloths of Heaven, 2023

Conversely, "Cloths of Heaven" (2023) is a diaristic record of time and process, an outward manifestation of the inner workings of the mind. As the eye careens across the dynamic surface, an underlying dreamlike structure emerges from the shimmering rectangles. Throughout, Canty's tightly regulated thread is imbued with a spiritual luminescence. For "Stare's Nest By My Window" (2019), which sources the W.B. Yeats' poem, Canty employs a tumbling block pattern to evoke the beehives built in the cracks of an empty house. Again, there is a concentration of timbres: colors win you over—a certain blue enters your soul, a certain red has an effect on your blood pressure. Individual veins and strata connect back to the lived circumstances of a real community. Figurative and abstract forms abut at certain points and weave together in a more integral manner at others. Up close, a pattern that would have been static and uniform is transformed into a spinning pinwheel, with a visual kick.

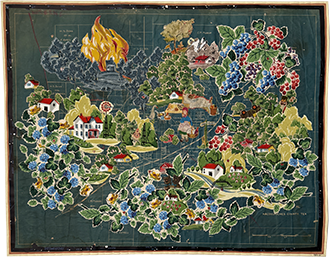

In the process, Canty shifts our perspective on the nature of wallpaper and collage—what it's for, how long it's meant to last, and what has the right to be beautiful. Issues of place, home and identity are plumbed in the collages. For Canty, the medium is a way to memorialize the past and to indicate its relation to the present and future in shifting images that resemble dreams. "Know Them By Their Fruits" (2025) combines narrative elements—a magician, an airplane, small fires and storybook children amid lush gardens—with star charts collected by Canty's grandfather. Here, and elsewhere, the artist manages to intimate the movements of a turbulent depth below a seemingly calm surface. The evocative cosmologies suggest a fragile world lovingly reclaimed and poetically reinvented for sustenance in uncertain times.

Heap of Broken Images is a seductive labyrinth of references and allusions. It is an increasingly rare aesthetic that embraces the deterioration of fragile materials and the wear and tear they display. These fragmented, searching and radiant works convey both harmony and dissonance. Yet all of them leave traces of light that are never quite extinguished from memory, a sense of wonder in the face of the ordinary. Canty asks us to look closely at what is discarded and imagine what could be.