La Vida Real (Real Life)

Cande Aguilar

February 28-April 4, 2026

Opening reception Saturday, February 28, 5-7 pm

Artist will be in attendance

Essay by Susie Kalil

It's intoxicating to stand in galleries filled with Cande Aguilar's open-hearted paintings that form La Vida Real (Real Life), his exhibition of some 30 mixed media works on panel at Kirk Hopper Fine Art. They set loose a cascade of associations—multilayered meditations on the complexities of human bonds, alternately intimate and tender, echoey, hypnotic and tangled. Eclectic images, high voltage colors, fast brushwork and skipping strokes are assembled with poetic precision and shocks of disorienting, fractured beauty. Energized abstractions and schematic heads, stick figures, flowers, rockets, watermelons, chain link fences, fragments of hand painted signs and printed slogans all teeter on a collision course and balletic movement, seemingly reckless decision and painterly finesse.

The Great Divide, 2025, multimedia painting with transfers on multiple panels, 48" x 72"

You're never quite sure what will happen in an Aguilar painting, which piques your interest, even if it can unsettle you. By the same token, the works are never an assault on the senses, but rather an assertion of life in its raw totality. Throughout, the Brownsville artist conveys what it means to be alive today, on the edge of borderlands, among conflicting histories and rival languages, amid new technologies and old traditions. There's friction, but there's also purpose; there's instinct along with calculation. As Aguilar understands it, art's best chance at sustainable survival is to stay scruffy, intuitive and imperfect, to flaunt its humanity. Our perception perks up at irritants and disruptions. As a matter of subsistence, we need to decide, and fast, what is a threat and what is simply a thrill. Aguilar aims to take advantage of those reactions. His art is a battle, and a balance, between order and chaos, passion and technique.

Much of the work negotiates how the present is buffeted by the past. Each painting reflects on the slipperiness of language and the precariousness of memory. Connection, as La Vida Real makes clear, is the point. And while there is no direct story, each composition is freighted with meaning—cyphers or manifestations of dreams, the subconscious and codes around which he is constantly circling. As a result, the paintings feel thoroughly dynamic. You get the sense of someone who rushes headlong into his work, over and over.

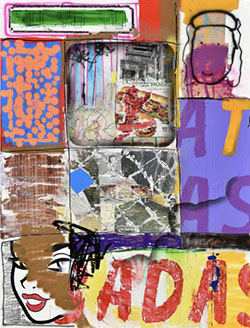

Clash, 2025, multimedia painting with transfers on panel, 48" x 36"

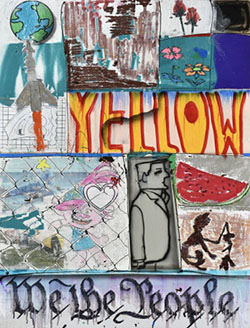

Mundo Gris, 2025, multimedia painting with transfers on panel, 48" x 36"

Aguilar refers to the immediacy of his paintings as "barrioPop," a kind of pluralistic scream that embraces the layered, contradictory world it emerges from, a world where cultures clash, remix and regenerate. For Aguilar, the barrio is "home base" and represents his Brownsville middle class origins. Pop takes the personal to the universal. "This is not assimilation," Aguilar says. "This is collision as creation. BarrioPop is born of borderlands geographic, linguistic, digital, emotional. Each piece is a visual overload: signs, symbols, slogans, colors, memories, memes all jammed together into compositions that feel like lived experiences. It borrows without apology—from punk flyers to Mercado packaging, from family altars to lowrider hoods, from Instagram filters to 1980s telenovelas. This is a movement of visual resistance—against flattening, against erasure."

To that end, Aguilar depicts an environment that is at once recognizable and strange, like when a familiar map becomes scrambled. At KHFA, you may feel yourself approaching the borderland between ordinary consciousness and that never land of the outsider psyche. He uses each panel as working surface, covering it with drawings, scrawlings, slashes, drips, transfers, images from his children's coloring books and legos, graffiti glyphs and the clattering "rotulos" signage. Just a glance around the galleries tells you this stuff is loaded with gut-clutching qualities eager to expose the vert bastions of entrenched power.

From the desperation of the Rio Grande Valley borderland, Aguilar creates a formidable visual and verbal lyricism. To be sure, there is something gripping about his work; it grabs you viscerally, yet insinuates a poetic understanding of the plight of souls. Indeed, only a few artists are able—or willing—to jump off the proverbial cliff for the wonderful and terrible freedom that can shock one moment and infiltrate a sense of being the next. Yet directions in the movement toward an authentic street art continue to be thrust from below, from a life begun quite literally underground by artists who stake their claim on a postindustrial world.

Untitled, 2026, multimedia painting with transfers on panel, 48" x 36"

GO, 2025, multimedia painting with transfer on panel, 48" x 36"

Aguilar, a self-taught artist, grew up surrounded by generations of musicians. His father, Candelario Sr., played bajo sexto (electric base and guitar) for over thirty years with a conjunto band. The Texas-Mexican "conjunto," a genre of musica nortena, was developed by Tejano working class musicians who adopted the accordion and polka from 19th century German settlers in Northern Mexico, later incorporating canciones rancheras (ranch songs), the bolero, and other musical forms, including jazz, to its repertoire. Unique to the border region, conjunto music, with its precarious balance of structure and improvisation, opened the door to Aguilar's creative world.

As a young boy, he tagged along with the Gilberto Perez y sus Compadres band as it played in ballroom dances across South Texas. At age six, Aguilar was given an accordion by his grandfather, Anastacio Aguilar. In 1984, he made a stage debut alongside his padrino (godfather), Gilberto Perez, who had gifted the teenage Aguilar with his treasured accordion, nicknamed "La Killer." Over the years, Aguilar found himself on stage with Narciso Martinez ("El Huracan del Valle"), founder of conjunto music, as well as musical legends Ruben Vela, Tony de la Rosa and Ramon Ayala. Aguilar's love of the accordion led to the formation of his own Tejano band, "Elida y Avante," whose landmark debut albums achieved gold and platinum sales.

When the band broke up in the late 90s, however, Aguilar decided to channel the conjunto masters he had watched over the years into making tangible forms of art. For Aguilar, the double rows of the accordion buttons provided a direct link to the compressed space of abstraction. Light, shadow, color and composition are key elements, of course, but he also sensed the sheer fireworks that our "climate of language" and cultural narrative of an intractably divided nation could set off. Aguilar mashed together what he heard and saw in the subtropical city streets and citrus groves: noise, mess, dirt, humor, ebullience, defiance. As Aguilar tells it, the music he played on stage came from the gut; he applied those same instincts to his paintings. Whatever blew the lid off, the desire to make images spiraled into art, much like a constantly running motor. Aguilar began to study the works of Pablo Picasso, Frida Kahlo, Rufino Tamayo, Andy Warhol. Roy Lichtenstein and Robert Rauschenberg in art books. There are also plain debts to John Valadez, Frank Romero, Patssi Valdez and other Los Angeles area Chicano artists.

While the pace is breakneck, Aguilar's compositions have a feeling of measured contemplation that balances savvy impulse and practiced smartness. Like a number of talented artists who aimed to blur the distinction between art and pop culture, Aguilar mixes things up, only on an unusually personal level. He amalgamates sources from a tough vernacular into densely choreographed scenarios that accelerate as frenetic rhythms.

Without a doubt, Aguilar has an almost unfailing ear for language, be it hand painted signs from fruit and vegetable stands or incongruous snippets of Tex-Mex slang. Aguilar knowingly utilizes the aesthetic commandments that have practically become the mantras of postmodernity—to undermine, destabilize and transgress. Language and symbolic memory are the tools that allow us to be aware of being conscious, and hence circumscribe our understanding of art. Yet language is also the primordial word become flesh, the flexible skin of the mind, flayed, tanned and draped onto the armature of syntax. This is a culture, however, that doesn't make the word into a medium of discourse. The word functions instead as a shock, a register of pure emotion, an aggression that is auditory and mental.

In La Vida Real, words accumulate, and in their sprawl we can see our world, perhaps ourselves. Throughout, sly wit and unpredictable couplings send out probes into our minds for fresh associations. Some words float, other repeated letters and images are piled up like pickup sticks; secret meanings are encoded in compartmental sequences; letters loosen into a kind of sonic field.

For "Light Bug in My House," passages of unsettled dissonance are followed by soothing consonance, imbuing the entirety with moments of tension and release, a sense of respiration. Aguilar's images, like tones, exert a gravitational pull, a dynamic that similarly shapes the basic structure of musical scores. The letters "LB" in screaming yellow and red paint anchor the bottom of the piece. Figurative and abstract forms abut uncomfortably at some points and weave together at others. The overall effect is a powerful work that is startling in its lack of pictorial hierarchy, reinforced by eye-popping color. Thin washes of purple, orange and deep blue slice up the composition, while black squiggles dance between cartoony bananas, schematic heads and portions of cherry pie. Here and elsewhere, the chain link fence serves as Aguilar's overarching trope. Haunting faces of men and women are positioned cheek-by-jowl with a coloring book image of a panting brown dog. All of them eye us, just as we eye them.

A kind of porous exchange, the barrier refers to economic status of the middle to lower class, as well as the painful separation that occurs between youth and adulthood. As evident in the steady stream of news, fences along the border have been made higher still. But of course they will never be formidable enough. As Aguilar knows, border culture includes a deep fear, the fear of being seen, caught, asked for identification. The fear is so deep that many choose to look away while the law enforcement and "good citizens" stay alert for "undocumented neighbors." We are always negotiating: Who is one of us?" Who means the children harm? Is it the outsiders clamoring for a piece of what has been earned or the insiders hoarding advantages?

For Aguilar, everything is a matter of perspective. An untitled (2026) painting features a black and gray sketch of a suited businessman, whose high forehead and "comb over" hairstyle emulate that of Trump. Above the figure's head is the word YELLOW, a hand painted sign in neon yellow and red that can be seen at fruit stands outside of Brownsville. In this case, however, the word explodes as the negative equivalent of coward. At Trump's right is a cut watermelon, a reference to the plentiful growth of the Rio Grande Valley, as well as paintings by Rufino Tamayo, but also symbolic of the Palestinian people. Below the watermelon is an abstraction of Wiley Coyote, the cartoon figure who always failed to catch the roadrunner. Aguilar shows its legs and tail, but the coyote's head is firmly stuck in Trump's butt. At left, an animated cartoon child in pink and turquoise peers at us from behind a chain link fence. Hearts and flowers seemingly float in the ether and are jammed alongside a fragment of a car's wheel and yellow fender. Above, still more flowers, in addition to images of the global earth and a rocket, provide an admixture of danger, hope and the hidden beauty of urban border life. At bottom, the opening words of the Constitution's Preamble, "We the People," stretches edge to edge with melting, dripping letters.

The resulting shapes splinter, fuse and harbor even more condensed forms and gestures. Aguilar obviously isn't interested in easy ambiguity or ambivalence. Instead, his ephemeral images convey a sense of urgency through their clipped tone and bold foraging of local urban existence. In this way, the show's title painting, "La Vida Real" (2026), re-exposes the individual veins, strata and images that provide an immediate connection back to the lived experiences of a real community. Part of a series of smaller works, it utilizes a richly painted vine—all color and form in endless, fluid flux—winding through the chain link fence. At center is a white dove, representing hope and peace, surrounded by layers of yellow checkerboard and blue diamond shapes, pink and purple flowers, as well as emerald green foliage, the symbol of human growth. The painting holds us in place, suspending disbelief to encourage all kinds of imaginative leaps.

Aguilar seems to be measuring up close, then at a distance. This tension—itchy, under-the-skin—gives his work the agitated and unpredictable quality of something experienced for the first time. Throughout La Vida Real, Aguilar balances the vital, pulsating energy with an unmistakable eloquence of touch. Evidence of the hand, of course, represents the personality and very soul of the artist. He re-empowers the hand, making it a seismographic recorder of the eruptions and tremors on the fitful paths of his nerve endings. Aguilar's charismatic vitality is always a few steps ahead, inviting us to chase after it.