Roger Winter at 90

May 31-July 5, 2025

Opening reception Saturday, May 31, 5:00-7:00 pm

Artist will attend virtually

Disko Bay, 2013, oil on linen, 60" x 108". From the Collection of Elise and Burk Murchison

Essay by Susie Kalil

Roger Winter is an artist of searingly original visions that combine formal rigor and spiritual mystery. Time's passage, the preciousness of the natural world, the beauty of mundane things are all hallmarks of his work. The philosophical questions that emerge from his paintings, drawings and collages deal with our identity and existence, our solitary state in the world, our limits in space and time. Winter's art explores the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves: our families, our country and the porous border between history and myth. The everyday fears and anxieties that shadow us on our awkward trip through time often feel enormous, even cosmic. For over seven decades, however, Winter has endeavored to find images and situations that give form to those metaphysical yearnings.

In honor of Winter's 90th anniversary, Kirk Hopper Fine Art is pleased to present a retrospective exhibition that highlights the Texas artist's prodigious breadth and great wingspan. Joining the thirty works on view, ranging from 1965 to 2025, are a number of major paintings generously loaned by Dallas collectors who have supporte—and celebrate—Winter's magical powers of storytelling to provide both solace and transcendence. Like a writer or musician, Winter has developed an ability to be in the moment while standing apart as an observer, a novelist's eye and singer's ear for detail, a precise but elastic voice capable of moving easily between the lyrical, the vernacular and the profound.

Wooster Street, 2001, oil on linen, 26" x 96"

Taken together, Winter's art and life offer the possibility that an individual might pursue a creative, intellectual evolution—wide eyed and joyful to experience—even in elderly years. At 90, Winter is not afraid of change or to push the limits in a quest for self-discovery. Throughout his staggeringly productive career, Winter has never adhered to a signature style. All of his works manifest a sense of place and direct experience—Texas, Maine, New York, New Mexico, Iceland, Greenland—but also a sharpened sense of interior worlds, richly layered and nuanced. Throughout the decades, Winter has gone various directions with visionary skill—it's not a question of inconsistency, but openness and growth. "I've always felt that I should be who I was at any given moment," he says. "I have never imitated myself, but have moved forward in time and insights."

At the core of his paintings is a spiritual search that plumbs the depths of the human condition. Winter weaves tales together into tapestries that are intricate, beautiful and flawed—a deliberate strategy meant to convey the chaos of life, distortions of memory and the bright threads of meaning that can be extracted from the jumble.

Genuine originals—individuals who follow their own lights, make their own rules and create their own frame of references—are rare in the art world. To his credit, Winter has never sought the avenues which gauge success by sales, publicity or branding. He has resisted categorization, art world expectations and almost any kind of authority.

At KHFA, the visually arresting works reveal a complex story of how art is made by one person of protean energy over the stretch of time. We are struck by a fundamental generosity in Winter's paintings—visual hymns of passage, of solitude and connection. They project a sureness, elegance and passionate serenity that leads us to consider him as having moved into the first rank among living American painters.

Swan, 2015, oil on canvas, 52" x 72"

Roger Lee Winter was born on August 17th, 1934, the youngest of five boys and three girls in a white frame house on a red brick road that ran parallel to the Kansas-Missouri-Texas railroad track on the outskirts of Denison, Texas. Winter's father was a laborer in a Denison creosote plant that preserved cross ties and utility poles for the KATY railroad. His mother cooked, raised chickens and cows and worked in the garden with little help or money. Their water came from a well dug and walled by his father. It was the only source for drinking, cooking and bathing. They had no indoor plumbing—a two-hole outhouse stood at the back of their acre of land—all of them bathed in washtubs that hung when not in use on the sides of their four room house. The poor conditions would later give his paintings depth and dimension. For Winter, art has been a way to sort through those crosscurrents of his life—race, class, family.

His development has been nothing if not eclectic. At different points over the decades, his work has been inflected by Cubism, Surrealism, Magic Realism, Pop, Constructivism, Primitivism, Realism, Precisionism, Hard Edge and other idioms, all of which he combines and recombines in all sorts of ways. It helps to think of Winter as a kind of philosopher-carpenter with an inborn, almost esoteric love of paint as paint. He wants us to understand its sensuousness, while also grasping that paintings are essentially "built" from scores of decisions and details. Winter's path does not move in a simple arc, but meanders between his interior life and his life in the world, connecting dreams, reflections and memories. His realism butts up against his romanticism even as the existentialist in him has searched for ways to coexist with the artist.

It's impossible to account for the past century of Texas art without including Winter in the picture. Although he has been based in New York City for nearly thirty years, Winter remains the vital link between generations of Texas artists. At the Dallas Museum School, Winter became an important mentor to a young Stephen Mueller, whose buoyant, mystical paintings would later redefine New York abstraction. As an esteemed faculty member of Southern Methodist University, 1963-1989, his past students include nationally recognized artists John Alexander, David Bates, Robert Yarber, Tracy Harris, Gail Norfleet, Lilian Garcia-Roig, and Brian Cobble, among others.

According to Winter, however, it was the educators at University of Texas at Austin during the early 1950s—Robert McDonald Graham, Constance Forsyth, Loren Mozley, William Lester and Everett Spruce—who inspired his intellectual and creative ferment. "I learned how a painting holds together two-dimensionally," says Winter. "Everything had to be in the right place—how to locate space in relation to the canvas or page, and in relation to the edge. They taught me that every mark you make must relate to the four sides." Winter especially recalls the encouragement and influence of Robert McDonald Graham, who had studied with American regionalist Thomas Hart Benton. "He frequently invited students to parties at this house near Lake Austin. I would play guitar and Graham would sing along. At one party, he announced, "All of you know that Roger has a softer touch with a brush than I do." My God, that kept me going for years! He continued to critique my paintings even after I was no longer in class."

That "soft touch" and formidable discipline, by which Winter takes the measures of the picture plane, are evident throughout the works at KHFA. Each painting is a riddle of facts, choices, details and optical experiences. The more we look, the more we see and learn about the way Winter's mind works, how it moves around a painting—front, back and sides—touching and considering every point, no matter how small, and leaving little signs.

In Carousel (1965), the boys and girls holding ice cream cones while astride boldly colored horses become fulcrums around which geometric planes are structured. Forms seemingly appear and dissolve amid a welter of delicate brushstrokes. The animals, trees and foliage that occupy the pictorial field of an East Texas pond in Landscape with Bulls (1981) are integral to it, immersed in it, fusing with lyrical passages of gnarly trails and shimmering tangles.

Coney Island, 1985, oil on linen, 36" x 132". From the Collection of Tim and Nancy Hanley

Whereas Chisos Mountains (1983) evokes our romantic belief in the land as a guarantor of psychic and physical freedom, its layers of brown, green and white pigments hold the surface as a vibrantly transparent membrane. In Coney Island (1985), Winter depicts the edges of abandoned buildings, flat or angled roofs in rhythmic repetitions of horizontal, vertical and complementary diagonals, bathing the entirety with warm luminosity. The painting resonates a disquieting sense of loneliness that seems to endow the most mundane details of everyday life with yearnings.

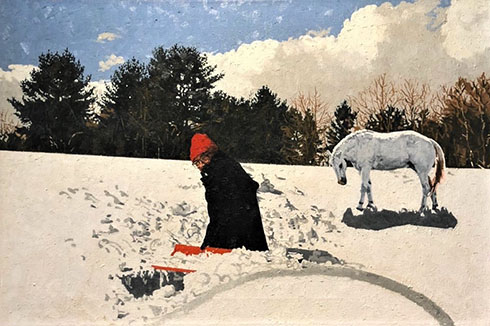

During the late 1980s and early 90s, Winter produced a number of enigmatic works in Maine that use the snowy landscape as a stagelike setting for a magic realist or psychic dreamscape with a "repertoire" of actors and recurring symbols. Winter Solstice (1990), a work of poetic strangeness and deep spiritual resonance, conveys a sense of place through mysterious, transformative images: an old house with light reflected in the window; a statue of an angel standing on frozen ground; a fox in the middle ground attending to something in the distance; a crackling fire burning in the snow. Such wondrous images are embodiments of mortal fears and our aching need to transcend them. Similarly, Self Portrait with White Horse (1993) depicts the artist wearing a red cap and black coat interminably shoveling snow. A white horse, symbol of light and mortality, bows its head as if to acknowledge the endless task.

Winter Solstice, 1990, oil on linen, 56" x 78". From the Collection of Susan H. Albritton

Self Portrait with White Horse, 1983, oil on linen, 24" x 36". From the Collection of Joseph Collins

Roger Winter at 90 also includes the magnificent Disko Bay (2013), with its phantom-like iceberg and crystalline blue waters, produced during a period of intensive visits to Greenland and Iceland. At KHFA, it is as if we are witnessing the slow formation—or disintegration—of nature's frail, subterranean forces.

It's important to note that the Nordic experiences encouraged Winter to condense his painting by reducing it to essentials. Like the 1930s Precisionist artists Charles Sheeler, George Ault and, especially, Ralston Crawford who portrayed factories and mechanical structures using a sharp-edged, simplified and precise technique, Winter also focuses on architectural and industrial themes characterized by a carefully reasoned abstraction in which subjects are streamlined to their basic, geometric shapes. Rendered in luminous tonalities, these "Construction Site" paintings of New York's forgotten corners are at once in motion and meticulously puzzled together. Their overlapping shapes, deep shadows, harmonious and dissonant mix of colors emphasize the rich, visual geometries of Manhattan, if not the very beat of the city.

Roger Winter at 90 reminds us what it means to live a life thoroughly, but also to make art for its own sake, out of inner vision and necessity. It presents Winter as a complicated, relentlessly rethinking experimenter, one who combines brain and hand in ways that artists still have everything to learn from.